Our Sùúrùgate Journey — Welcoming our Joy

우리의 대리모 이야기| Unpacking our Experience with Surrogacy| Episode 15 (2025)

“Infertility isn’t a footnote in my life. It’s a saga. Two doctoral degrees, a physician husband, and endless surgeries: ovarian cysts, fibroids, endometriosis. I’ve bled through it all. I was told, ‘You’re young, you’ll be fine,’ but culturally aware care was absent. When your pain is dismissed, your time slips away. We turned to IVF because scar tissue engulfed my ovaries, and no sperm could survive that environment. This isn’t a ‘journey.’ It’s survival. Surrogacy? It’s our truce. But don’t romanticize it. It’s messy, costly, and born from exhaustion”. Mo!— (2025)

DISCLAIMER:

This episode contains heavy themes—a heads-up to anyone who may be emotionally fragile or easily triggered.

I’m a mother of two, and neither of my children came to me through the traditional route. My first was through adoption, and my second was through surrogacy. It has been a rewarding experience — but not without trials and challenges.

As you can imagine, I have a lot to process. This will be my first time diving deeply into this personal and complex journey. We’ve discussed heavy topics on the podcast, especially infertility. Conversations like this help me sort out my feelings and thoughts. That said, some of what I share may even surprise me. I’m both the speaker and the observer, watching my truths take shape in real time.

A therapist once told me I’m an “external metabolizer.” I tend to internalize a lot, but once I start speaking, I begin to understand what’s going on inside me. That dynamic will show up heavily in this episode.

Before we go any further, I must say this clearly: this is my story. Please don’t take my experience and use it to shame or pressure someone else, especially anyone navigating fertility or family-building choices. This isn’t a blueprint. This isn’t advice. It’s not a “See? She did surrogacy — so should you” kind of thing. In fact, I am outright banning that mindset. Seriously — don’t do it.

I say this because it’s been done to me, and it hurts. People already know about surrogacy — they don’t need your unsolicited reminder or judgment. Share this episode only if you can do so with empathy and an open mind, not to make a point or push an agenda.

Above all: don’t use my story for evil. God is watching you.

What works for me may not work for you or anyone else. If you’re considering this path, please approach it safely. Talk to your medical provider. Talk to your partner. These are life-altering decisions — ones that can strain or even break relationships. Be careful. Be thoughtful. And above all, be kind to yourself and others.

A Quick Backstory

If mics could talk, the podcast would be no stranger to my journey, and all previous episodes would be linked below or in the show notes. Here's a short version for those new to this podcast who don’t know about me and my journey. We didn’t just jump into surrogacy. We tried everything. And I know some people love to ask, “Have you tried this? Have you tried that?” The answer is yes. Yes, we have. I’m not just speaking from emotion here — I come with receipts. I’m a trained pharmacist with two doctoral degrees: a PharmD and a PhD in Pharmacy. I know the science. I know what I’m talking about. And I’m married to an experienced physician. So when we say we struggled with infertility, we know it deeply, personally, and medically. That said, I’m not giving medical advice. I don’t even believe in giving advice. I’m simply sharing my story, and if something in it resonates with you or helps you, then take what you need.

Let Me Start from the Beginning

I was born in Nigeria in the 80s and married about 14 years ago. As a child, I somehow knew that my journey to motherhood would not be typical. Not in a bad way, but I remember telling my mom that I wanted to adopt someday. Of course, I got the typical Nigerian mother reaction: “God forbid. You will carry your kids.” But I always believed those two things weren’t mutually exclusive — you can adopt and still have children of your own. That sense of connection to people trying to conceive started early for me. My heart was drawn to women on that journey in church, in our neighborhoods, even among my colleagues at the pharmacy. Still, I had no idea how long and hard my path would be.

Surgery, IVF, and Loss

In 2009, two years before I got married, I had my first surgery. I remember always answering “none” when asked about surgical history with a sense of pride, and then from 2009 to 2023, I lost count of how many I had. I’ve dealt with recurring ovarian cysts (small fluid-filled bumps on the ovary), fibroids (noncancerous growths in the uterus), and even endometriosis (when tissue like the uterine lining grows outside the uterus). Each condition came with so much pain. And surgeries. There are so many that I’ve exhausted all the fingers on both hands counting them.

After the first laparotomy, which is a major open surgery to remove cysts from the ovaries, things got even more complicated. Scar tissue formed, and fluid started building up around my ovaries, making it hard for sperm to travel. The environment was hostile and polarized. Doctors placed an anti-adhesive film, hoping it would dry up and give us a shot. It didn’t work. So we moved on to IVF straight away. No IUI. Just straight to the big guns.

We had 17 eggs extracted, and after all the lab work, we ended up with about 10 viable embryos. I did a fresh cycle, implanted one, and didn’t get pregnant. I was devastated. I got the call from the nurse on a Friday afternoon while I was on the bus heading to class. I cried so hard. People sat next to me, but no one asked what was wrong. I felt so alone (realities of living abroad).

We tried again two years later. Bear in mind, I was still in grad school, with no IVF insurance coverage because I was in Texas — a red state, where fertility care isn’t prioritized. We were paying out of pocket, scraping together funds. That cycle worked. I got pregnant in 2014, just as I was completing my master’s. But at eight weeks, I miscarried. I bled so heavily, I thought I was going to die. I remember calling the nurse, and she said, “Well, you can go to the ER, but it sounds like it’s already been evacuated.” The earliest I could be seen was Monday. That loss changed everything.

From then on, it was a series of failures — more transfers with the frozen embryos — none successful. In 2018, we did one last transfer. I got pregnant again, but this time I was in Ireland, and I miscarried. That was the last time I ever got pregnant. It’s been seven years.

If you know me, you know I’m a triple-A type. I get things done. Efficient, driven, a little bit of a control freak. The kind of person who, if you tell your dreams, I’d hammer you till it’s done. Nothing prepared me for the depth of grief that comes with infertility. I cried so hard during my first miscarriage that I ruptured my eardrum. I still have ringing in one ear to this day. No one—not even your spouse or your mother—can fully understand that pain.

The Mock Cycle and Letting Go

After that last pregnancy loss, we tried a mock cycle with a more culturally sensitive doctor in Oklahoma. He suspected my progesterone levels weren’t supporting implantation. We tried adjusting them, but it didn’t work. I remember getting the negative test results, walking to the fridge, grabbing a wine glass and wine cubes, and pouring myself a drink. I told myself, “Well, I’m not pregnant. Might as well drink.” That was my mindset at that point.

Eventually, we talked about fostering and adoption. My husband came around to it, and we started fostering. After a few placements, we adopted one of them — our daughter, Ariifeoluwa Adedipe. My first child. One of the greatest loves of my life.

Adoption is its kind of grief, but also an incredible sort of love. The ability to love someone you weren’t biologically programmed to love shook me. I didn’t think I was capable of it. But it became my first path to motherhood. And it was okay. But my husband still wanted to try again.

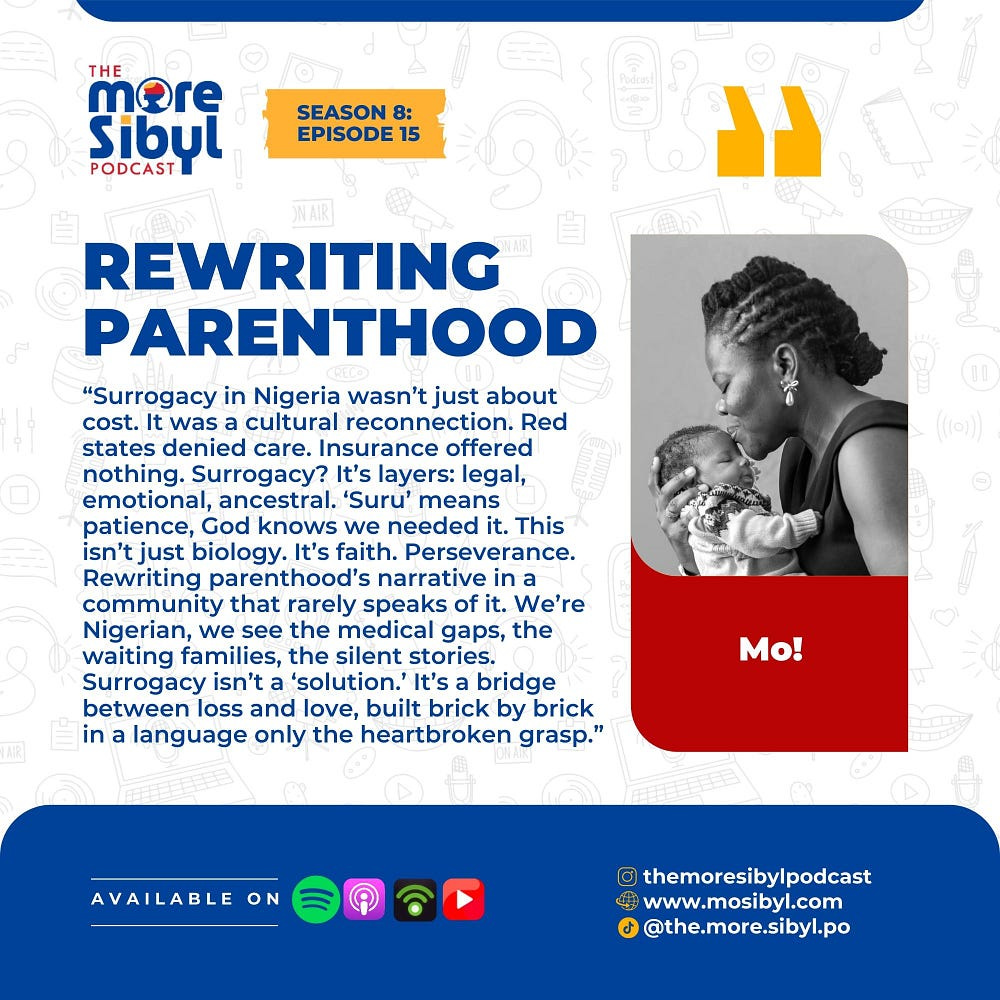

Introducing Sùúrùgate: A Journey of Patience, Faith, and Unspoken Paths

This is the first episode in a new series I’m calling Sùúrùgate — and trust me, I didn’t choose that name lightly. Before I dive in, I wanted to lay the groundwork for why this story matters. Sùúrùgate is more than just a surrogacy story. It’s a story about waiting, hoping, and walking a path filled with emotional, cultural, and legal complexities. As a Nigerian-born American, I’ve experienced firsthand how surrogacy is often whispered about — if it’s spoken of at all — especially in African communities. But I’m here to change that.

This five-part series will take you inside our surrogacy journey. I’ll share it all — the highs, the lows, and the unexpected turns. You’ll hear from experts who guided us through this process's legal and medical sides. And hopefully, we’ll even hear directly from a surrogate to understand what it means to carry a child for someone else, and why some choose to serve as surrogates for commissioning parents.

Now, why the name Sùúrùgate? It’s a play on two words: surrogacy, of course, and sùúrù, which means patience in Yoruba. Because this journey has demanded more patience than I ever thought I had. Waiting, adjusting to change, trusting a process I couldn’t control — this road has stretched me in every direction.

So no, this isn’t just a story about reproductive technology or contract terms. It’s about endurance. It’s about faith. It’s about navigating the long, quiet road to parenthood that so many walk in silence. And in this first episode, I take you back to the beginning: why we chose surrogacy, why we went back to Nigeria to do it, and what we expected versus what we faced. It’s personal. It’s layered. And by telling it, I hope to open up a long overdue conversation in African and diasporan communities.

When the Heart Leads: Choosing Surrogacy

By the time we reached 2021, we had already been through IVF, adoption, and fostering. That year marked a pivotal shift — our daughter was still in foster care, and we were close to finalizing her adoption. For those unfamiliar, fostering in the US means being a temporary legal guardian — you haven’t formally adopted the child, but in every practical and emotional sense, you’re their parent.

During that period of waiting, we decided to explore surrogacy. It wasn’t a decision we came to quickly or easily. We began by comparing the cost of pursuing it in the US versus Nigeria. Given that we’re both Nigerian-born, Nigeria felt accessible and familiar. My husband trained as a physician there, and I, a pharmacist, was also well-versed in its healthcare system. We also had the support of family. The financial disparity was stark: surrogacy in the US can run from $250,000 to $500,000. Nigeria was a fraction of that.

Because we wouldn’t be physically present throughout the process, we tapped into our medical network to find a trustworthy team. We carefully narrowed our list down to five doctors. I shared my full medical history with each of them. The doctor we ultimately chose came highly recommended by our close friend Busolami, a nurse who had worked with him before and spoke highly of his ethics and results. But what stood out was that he was the only one who had read my entire file.

He brought things to my attention that no one had mentioned before. Like I said, I’ve had multiple surgeries, so many that I’ve lost count. Robotic laparoscopies to drain cysts, surgeries to relieve the pain from endometriosis, and ovarian cysts. If I showed you my body (which I’m not going to do), you’d see the marks, small holes left from each procedure. And this doctor asked me: “Did anyone ever talk to you about freezing more eggs before all these surgeries?”

No one had.

He explained how those surgeries, though necessary to save me from the agony of endometriosis, had affected the quality of my eggs. My AMH level — anti-Müllerian hormone, which indicates egg reserve — was that of a woman in her sixties. That’s because every time I had surgery, it damaged my ovarian lining, stripping away potential and hope with it. Let me explain: when a female child is born, she has the most eggs she’ll ever have. From that moment on, the count only goes down.

So if my story sounds like yours, please ask your doctor about freezing your eggs. I repeat, I’m not saying do it; this podcast doesn’t offer medical advice. But have the conversation.

Given my history — stage 4 endometriosis, recurring ovarian cysts, and multiple pregnancy losses — it became clear that outsourcing the pregnancy through surrogacy might be our best option. But it wasn’t a decision we rushed into. It took two years of conversations, research, and profound emotional reckoning before we finally said yes.

At first, I clung to the hope that if I just kept trying, I could carry a child to term. That’s what many of us believe, especially when we’re repeatedly told to “just keep trying.” But after many failed attempts, I had to get brutally honest with myself. I realized I needed dedicated care for my gynecological issues, something I didn’t have before. There’s a lot of focus on seeing a reproductive endocrinologist when trying to conceive. Still, I needed a primary care provider who understood my full history — a gynecologist, a family physician, someone who could help me make the tough calls.

I learned that every treatment to stop my endometriosis — whether it was birth control or Lupron (hormone-suppressing medication) — also prevented me from getting pregnant. Lupron, in particular, was brutal. It gave me menopausal symptoms: my bones ached, I was dry all over, and I felt like I was losing myself. But those treatments were essential to manage the pain. I had to choose: stop the pain or keep trying to get pregnant. Making that excruciating choice was my reality for years.

Emotionally, coming to terms with surrogacy was hard. At first, I felt like a failure — like my body had let me down in the one job it was “supposed” to do. But therapy helped, and my daughter helped even more. Loving her, a child I didn’t carry, showed me the truth: Motherhood is about the heart. If I could love her enough to give up my liver or my brain for her, no questions asked, then I could love another child brought to me through surrogacy just the same. I realized that surrogacy wasn’t giving up. It was a path forward.

In many African cultures, the belief is that you should carry your child yourself, that blood ties are everything. That kind of pressure and misunderstanding can complicate things. But we had to choose what was right for our family. We first shared our decision with our immediate family, who were incredibly supportive, just as they were with our adoption journey. I know not everyone is that lucky. If you face opposition, remember that people respond based on their understanding of the world. Do what’s best for you.

We’ve never walked the typical path. And this — surrogacy — just became another chapter in our story.

Navigating Surrogacy Ethically and Legally

Still, I had serious concerns about going to Nigeria for surrogacy. The more I researched, the more uncomfortable I felt. When we visited the clinic in Nigeria to speak with the doctor, he was honest with me. He told me that there were no strong laws in Nigeria protecting surrogates. The system there often treats surrogates like house helps — omo odo — with agents acting as middlemen between the clinics and the women. These agents are paid directly; if at all, they give the surrogate very little of that money. Women carrying babies aren’t properly housed, fed, or cared for.

I couldn’t, in good conscience, be part of something that dehumanized the very person helping bring my child into the world. The doctor didn’t sugarcoat it — he told me plainly, “That’s how it’s done here.” That conversation haunted me and made us pause. We sat with that reality for two years and explored alternative ways to move forward. I’ll talk about those changes in a future episode.

When we eventually decided to go forward with surrogacy, we signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the clinic in Nigeria. I shared this with the doctor we would work with, and thankfully, the clinic offered a comprehensive package. This included legal services, which are crucial to establish upfront, and help find a surrogate through their partnered agency. The clinic handled all of that. Our role was to pay for the services and provide the necessary samples to create the embryos.

Our decision to go with Nigeria came down to cost, legal considerations, and cultural familiarity. Nigeria was more affordable, we understood the medical landscape, and we had family there. But beyond cost and culture, we were incredibly intentional about doing this ethically and with integrity. That meant going the extra mile to ensure we weren’t contributing to a system that exploits vulnerable women. If you want a baby and don’t care how it happens, this part of the story may not apply to you. But it's essential for those of us who want to do things right and sleep well at night knowing we didn’t cut corners or ignore injustice.

Even though Nigerian laws around surrogacy are weak, that doesn’t permit us to behave carelessly. I wanted to ensure that when history looks back, I did right by everyone whose path crossed mine. And that includes the surrogates, who gave me the most precious gift, something I couldn’t give myself. A surrogate to me is sacred. Whatever their reasons for doing it, I’ll never speak down on them. They laid their lives down — literally — for something I couldn’t accomplish on my own.

As U.S. citizens having a child abroad, we also had to consider legal issues. The U.S. confers U.S. citizenship by birth on American soil and by blood, depending on the parents’ citizenship. Because our child was not born in the U.S., we had to go through a determination process with the U.S. embassy. They wanted to see everything — when we started thinking about surrogacy, all our signed documents, USple collection dates, and how those aligned with passport records.

Mosiblings, I can’t stress enough the importance of keeping thorough documentation. I have a folder on my computer with every timeline, passport, and legal agreement. Even name changes mattered; I travel often and go through passports like notebooks, so keeping every version was key.

We began the process in 2023. The clinic found us a surrogate and implanted two embryos. We got pregnant. And when I found out we were having twins, I was terrified. It was a wild moment, having spent so long trying to conceive, and then suddenly being scared of actually having babies. I remember feeling like, “Anty, pick your struggle.” But that anxiety was real.

The clinic helped make the experience smoother by creating a WhatsApp group to communicate with a nurse assigned as our point of care. She provided updates on the surrogate’s health and antenatal visits. I have to give credit to the doctor here — when I raised my concerns about the ethical treatment of surrogates, he understood where I was coming from. He suggested we could send additional funds directly for the surrogate’s welfare. Honestly, he told 50,000 naira initially — not a lot, and we did more. We couldn’t pay them directly, but we ensured they had food and essentials, and our nurse facilitated all that. That step meant a lot to me.

Our First Attempt (Another Kind of Grief)

I remember waking up one morning at 3 a.m. in August, something I never do, and for the first time, I felt ready to lean into the pregnancy wholly. We were 14 weeks in, and everything seemed to be going well. I thought, “Let me finally download the BabyCenter app and get involved.” It felt like a small but meaningful step toward accepting the reality of what was happening — that we were doing this and were almost at the halfway mark.

That same day, we lost the pregnancy.

The emotional weight of that moment is still hard to describe. I had never carried a pregnancy in the past eight weeks, so 14 weeks felt like a milestone. We had been cautious, deliberate, and hopeful. But what happened that day was a painful reminder of how fragile this process can be.

There were multiple layers to what went wrong, and I’m sharing this because no one should have to learn these lessons the hard way. After the surrogate became pregnant, she was transferred from the fertility clinic to an antenatal clinic — standard procedure in Nigeria, since few clinics manage both services. From that point, our primary contact was a nurse helping us unofficially, not someone assigned by the antenatal clinic.

A scan had been scheduled, but when the surrogate got to the hospital in Ogudu, the sonographer wasn’t available. She was told to return another time. In the gap between that failed appointment and the rescheduled scan, something happened that wasn’t caught in time. By the time they went back, one of the twins — fetus A or B, I can’t even remember now — was confirmed gone. At first, we clung to the hope that the other was still alive. But the HSG levels, which should rapidly increase with twins, were steadily falling. Not low enough to confirm a complete miscarriage yet, but enough to tell us that something was wrong. Eventually, both were gone.

It felt like a cruel joke. I had just started participating — downloading the app, learning about fetal development, and reading about how the lungs and head formed—that same day.

At this point, I felt a combination of guilt and grief. Did I jinx it? Did I bring bad energy into the process? I kept that guilt to myself for a long time, not even telling my husband. It felt like some cosmic punishment, though I had no idea what for.

People might try to assign blame in situations like this — maybe the surrogate did something wrong? But I refused to go down that path. It doesn’t even make sense. Most surrogates in Nigeria are already vulnerable. Many have low levels of education, which unfortunately makes them more susceptible to exploitation. They don’t always know the risks they’re taking on: death, sepsis, losing their fertility, etc. And because agencies usually require that surrogates have had at least one child before, these women have something very real and very personal at stake. Why would any of them jeopardize their health and future like that?

The grief I felt from this loss was unlike anything I’ve experienced. I’ve had my pregnancy losses, but this was more complex — more layered. I wasn’t just mourning the babies. I was mourning the process, the hope, the trust I had placed in a system, in people. In that pain, I wrote a letter to our surrogate and asked the nurse to deliver it. I told her I didn’t blame her—not one bit. I honored her. I thanked her. I told her my heart went out to her for having to go through this trauma alone, especially after having to undergo a D&C (dilation and curettage) at 14 weeks.

We sent her a little bit of money. It was the least we could do. That was our first experience with surrogacy. And we lost our twins.

You Can’t Do This Alone

In January 2024, we tried again. One of the most significant shifts between our first and second surrogacy journeys was the decision to bring more people in. I stopped trying to manage everything by myself. This theme carried us through: You can’t do this alone. It’s a lesson I didn’t know I needed, and it came from voices I trust deeply.

After everything that happened the first time, I turned to my friend Temi. And if you’ve followed my story, you’ve probably heard her name before. She’s the reason I started this podcast—one of the most influential people in my life. Temi connected me with Busola, a mutual friend from our days at LUTH — Temi and Busola studied nursing, and I studied pharmacy. Same circle, same hustle.

Busola suggested we try a new approach: hire a midwife as a liaison between us and the surrogate. That way, the surrogate would have someone on the ground who understood the process medically and emotionally. That’s how Chidinma entered our lives—a licensed midwife who took on the role and did it with incredible compassion.

We set up a WhatsApp group in April 2024 — me, Busola, Chidinma, and my husband. That little chat turned into a lifeline. Busola, especially, became my warrior. She checked in on me constantly, asking me the questions I didn’t even know I needed to answer. How are you doing mentally? What’s going on in your head? What are you afraid of? I couldn’t face those questions on my own; I was too far in grief and fear. But Busolami reminded me that I needed to be firm and have faith. I couldn’t let my past experiences paralyze me. I want to use this opportunity to encourage anyone going through this, with tears in my eyes, you have to be firm. You must approach this thoughtfully, prayerfully, and with people at your side.

Through her, through speaking up and letting people help, I began to function again. You need a village. Not just a supportive town, but one that will go to war for you.

Chidinma did just that for our surrogate — let’s call her Jane. She visited, built a relationship with her, and ensured a real connection beyond the transaction. We learned about Jane’s life, her children, her needs, and her reasons. We didn’t want to relieve our pain at the expense of her humanity. Chidinma helped us make thoughtful, informed choices that accounted for cultural context, care, and dignity. She helped correct my diasporan instincts, which, even with good intentions, might have led to unwise actions.

We invested in Jane's well-being instead of just throwing money at things. We paid for her antenatal care and her medications, using my background as a pharmacist to ensure she received authentic, high-quality drugs. We covered her therapy during and after the pregnancy. She still had a session a week before the recording of this episode.

We covered her accommodation, two years upfront, which is how it’s done in Nigeria, and helped her develop a business plan to support her financial independence post-delivery. Because even though the agency pays something, it’s not a life-changing sum. We didn’t want her to feel like surrogacy was the only option left. We supported her with monthly stipends, bought food while she was hospitalized, and when I traveled from the US to Nigeria, I brought gifts for her kids — school supplies, essentials. I even wrote her a letter: I honor you. You will always be part of our story.

And that’s the truth. She doesn’t know who we are, but I know who she is. I carry her in my heart.

It’s still hard. I wrestle with the guilt of benefiting from someone else’s vulnerability, even with all the steps we took to improve. But I share this because I want others to know: there are more humane ways to walk this path. You need your people. You need to be thoughtful. And most importantly, you cannot do this alone.

“Surrogacy demanded humanity, not just contracts. We funded therapy, safe housing, and a business plan so she wouldn’t need surrogacy again. Yes, we used a broken system, a truth I grapple with, but rejected its exploitation. Monthly, we sent extra funds, stocked her children’s school supplies, and honored her in letters. Guilt remains, but action matters. Surrogacy shouldn’t be transactional. It’s seeing the person, not the process. Even in desperation, dignity is essential. You don’t mask harm with money, you dismantle it deliberately.”

Learning to Sit in Joy

After everything — after all the planning, the prayers, the setbacks, the help, the heartbreak, and the hope — we welcomed our baby boy in November. I thought I’d be overwhelmed with joy. But joy didn’t come easily. His name even has “joy” in it, not just as a nod to celebration but as something I deeply needed. Like my daughter, whose name is rooted in “love” to remind me of God’s enduring love, my son’s name was intentional — a prayer I was trying to grow into.

The hardest part for me was connecting. I was going through the motions — traveling to Nigeria with my daughter, surrounded by family, preparing for a moment that should have been all smiles — but inside, I was numb. I’d waited nearly 14 years for this miracle, and when it finally came, my heart had hardened from everything we’d endured. I could recognize that this baby was mine, but the feelings didn’t immediately follow. My head understood it, but my heart needed time.

I remember watching my daughter’s reaction when she met him for the first time at the hospital. We’d tried explaining to her that she was getting a baby brother — even though I didn’t have a bump, the crib was getting set up, baby clothes were being folded, and the excitement was building. But how do you explain surrogacy to a five-year-old? We did our best, but her joy when she finally saw him was something else. She looked at him in awe, saying, “That’s my brother?” I was stunned by her fierce love and protectiveness. I wanted that childlike joy.

But it wasn’t immediate for me, and I had to remind myself that this was my story, not one to be ashamed of. I hadn’t just been waiting for a miracle all those years; I forgot to ask God to let me receive it joyfully. My heart had been so closed off, so tired, so calloused. Like in Ezekiel 36, I needed God to take out my heart of stone and give me a heart of flesh again.

Slowly, that connection started to grow. Little things helped — seeing him smile, feeling him follow my voice across the room. My mom and mother-in-law were around, which meant I had help (and barely a chance to do much myself!). But I got moments—bathing, feeding, and holding him close. These everyday acts helped me start to know him, and knowing him helped me feel the joy.

It came in pieces, not all at once. But it came.

Owning Your Journey Without Shame

I’ll stop here for now, but before I go, I want to leave you with a few reflections from this part of our journey. Post-surrogacy has brought a lot of emotional shifts — not just for me, but in how society reacts too. There’s a weight to it all that people don’t often talk about. We went to Nigeria because of the baby — trying to get his passport so he could fly back with us to the U.S. Spoiler alert: it is an excruciatingly long process, and I’ll get into all of that in a future episode, including how we prepared for interviews and what it took to bring him home legally as U.S. citizens.

But right now, I want to talk about what it means to stand firm in your choice, especially as a parent. When we took the baby in for his vaccinations and circumcision, we were met with a lot of unsolicited opinions. Whenever they weighed him and saw his health, the nurse asked, “Is he on breast?” And saying, “No, formula,” would almost turn into a shaming session.

I wasn’t going to breastfeed. That was my personal choice. Sure, there are options if you want to induce lactation, with meds and all that. But I didn’t want to do any of it. And of course, I was questioned for my choice. It’s exhausting how people shame others based on their delivery methods, their feeding choices, and everything in between. Not everyone can breastfeed, even when they try. And that’s okay.

You have to learn to be patient with yourself, understand yourself, and stand tall in your decisions. Not everyone will understand or support your path, and that’s fine. Because at the end of the day, your path is your path. There’s no single right way to become a parent. Whether through surrogacy, IVF, adoption, vaginal delivery, C-section — each journey is valid.

I’ve learned that grace becomes easier to access when you finally accept your story for what it is. My prayer for you, if you’re listening and walking your complex path to parenthood, is that you’ll find the strength to do just that: embrace your story and walk it with peace.

If you’d like me to dive into anything specific in future episodes — especially related to this journey — please comment and let me know. There’s still more to unpack, especially the logistics and surprises of bringing our baby home.

Until then, please be safe and take care of yourselves. And if this was your first time listening, I truly hope it was worth your time. Don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook, and check out the podcast on all major platforms. You can also explore previous episodes on fertility and more over at www.mosibyl.com. See you in the next episode!

🅻🅸🅽🅺🆂:

Download: https://mcdn.podbean.com/mf/web/u98ukybrrd2t4ws3/SUURUGATEMoNOLOGUE2025.mp3

Or on the website: www.mosibyl.com

My past episodes on my Fertility Journey: