Fatherhood, Feminism, and Faith

사랑, 순종, 그리고 상실| A Candid Conversation — The One with Dr. Ikechukwu Okoro | Episode 20 (2025)

“I come from a family of five children. My dad lived outside the country; he visited once a year. Growing up, you understood that this was a sacrifice for everyone’s betterment. Being the fourth child and third boy, I always felt I was the one who was dispensable. When I was naughty, my mom would say, ‘I have three other sons; I’m not counting on you.’ It registered that nobody was giving me handouts. I wasn’t needed, per se. I had to work hard, stand out, and be the good boy. She’d tease, ‘If it were slave trade times, I’d have sold you.’” — Dr. Okoro (2025)

BLOG POST

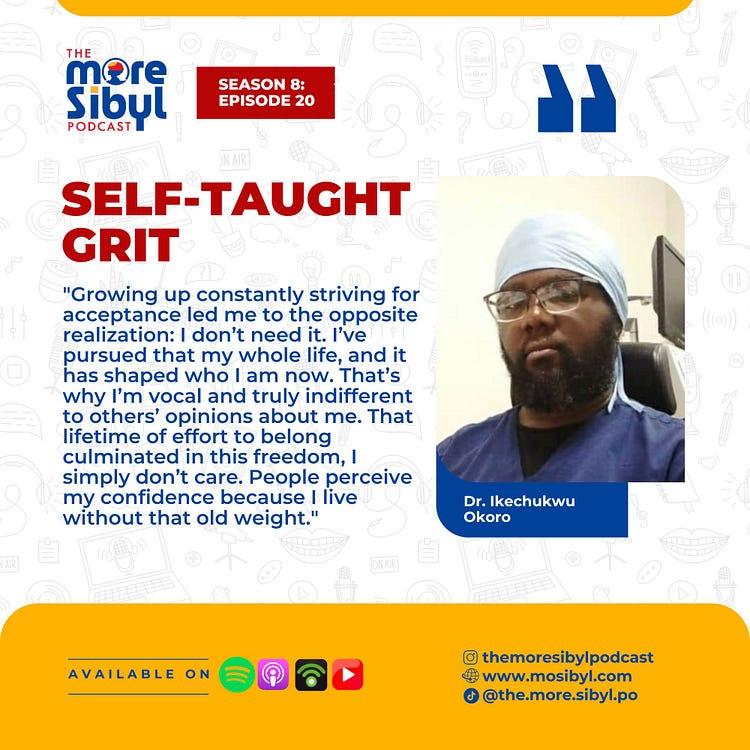

It’s always a delight when I bring close friends to the podcast, and in this episode, I’m joined by a dear friend of 15 years, Aikay — Dr. Ikechukwu Okoro. I met Aikay during my NYSC days in Ibadan. It’s not every day you find a fellow corps member who shares your love for the satirical madness of Family Guy, so we bonded instantly. Our connection deepened through countless intelligent conversations.

These days, Aikay goes by Dr. Ikechukwu Okoro to his patients — he’s a practicing physician in the UK. One thing about him: you can always count on him to wear his mind out in the open. He calls himself a “common sense advocate” and a self-proclaimed human rights activist. His opinions aren’t just sharp — they’re so pointed, they can make you laugh, gasp, or block him. Sometimes, all three at once. Trust me, you’ll need more than a stethoscope to keep up with him.

The Making of a Vocal Man

Aikay grew up in a family of five children — four boys and a girl. He was the third son and fourth child overall. His father lived outside the country for most of Aikay’s life, visiting only once a year. The rest of the family would occasionally visit as well. However, as he put it, “The family structure is not exactly the same when everyone is not around.” Still, they all understood that his father’s absence was a sacrifice made for the greater good of the family.

Aikay described feeling like the expendable one among his siblings. His position in the family and the way he was spoken to reinforced that idea. “I always felt like I was the one who could be done without,” he admitted. His mother’s teasing remarks, like “I have three other sons,” planted seeds of doubt early on. She would even joke that if he had lived during the time of the slave trade, she would have sold him. As a child, he believed it. Those jokes shaped how he saw himself — expendable and unneeded. That belief pushed him to work harder, to stand out, to be the “good boy,” and to earn his place.

As he grew older, he began to recognize how much he actually resembled his father, not just in appearance, but also in personality. They bonded in their own quiet, unique way. Sadly, Aikay lost his father last year.

I asked him next whether he had given up that deep-seated desire to be accepted, the need to prove he belonged. His answer was honest and insightful. He compared it to what happens when someone grows up poor and then suddenly has money. There’s often a phase of overcompensation, trying to buy everything you once lacked. Eventually, they find that it wasn’t as important as they thought.

After years of trying so hard to belong, he outgrew the desire entirely. He said it plainly: “I really don’t care about people’s opinion, per se, about me. I’ve seen that all my life.” And that’s why he’s so vocal today. His boldness, his bluntness, the way he says exactly what’s on his mind — it all comes from a long history of needing to be seen, until one day he decided he didn’t need permission anymore.

That’s Aikay. Unfiltered, unapologetic, and completely done trying to earn a seat at the table. “A whole lot of who I am today comes from the fact that I have been this person all my life. And at this point, I really don’t care… I can say everything I want.” And he does.

Choosing Medicine and Honoring Legacy

One of the most powerful parts of my conversation with Aikay was hearing the story behind why he chose to study medicine, even though, as he openly confessed, he doesn’t have a “medical bone” or “scientific bone” in his body. Aikay is, at heart, an artist. He draws professionally, and he’s also a writer. His world is firmly rooted in the arts. So, how did someone so deeply passionate about creativity end up in the medical field?

It all traces back to his father, a man Aikay described with a reverent mix of admiration and disbelief. Aikay’s dad saw what many people couldn’t at the time: that Nigeria’s future might not unfold as optimistically as hoped in the wake of its democratic rebirth. Despite no early signs of crisis, his father foresaw instability and urged Aikay to pursue medicine, not to stifle his dreams, but to secure a stable foundation in case those dreams didn’t pay off. “Medicine doesn’t stop you from doing whatever you want to do,” his dad had said. “Have something to fall back on.” Aikay resisted at first, assuming it was just a matter of paternal insistence. But in hindsight, he admits, “I’m glad I took that advice.”

That advice is even more poignant when you consider the incredible story of his father’s own journey. This man never attended secondary school — never saw the four walls of one. He grew up in a mud house, lost his father early, and was sent to Lagos to serve as a houseboy. There, without formal schooling, he taught himself to read and write by using the textbooks of the children he served. He eventually took a typing correspondence course, became one of the typists on Allen Avenue, and began supporting his family.

What triggered his decision to go back to school was a moment of provocation. A relative he was sponsoring for school questioned his own educational sacrifice. That stung — and sparked something. Aikay’s father, already in late adolescence, took up A-levels without any prior formal education. From there, he eventually left for the UK and studied medicine.

I was floored. “Who was this man, Aikay?” I asked aloud. It doesn’t sound real? Studying medicine without a secondary school education?

But the story didn’t end there. Aikay’s mother was just as formidable. At a time when she held a master’s degree and a good job in the ministry, she chose to leave it all behind so the family could keep their university quarters when Aikay’s dad left for further studies abroad. She took the fastest job she could, teaching at a staff school. After, she launched into a multi-pronged hustle. At the same time, she ran a poultry, bakery, restaurant, grocery store, and a tailoring business — while raising four toddlers. She would sew at night, as a Nigerian tailor, she tried to meet up with her clients’ demands, all while managing the home and finances. Every naira she made went to keeping the household running and supporting her husband’s education abroad.The respect Aikay’s father had for his mother was immense. And rightly so. “You don’t see this kind of thing anymore,” Aikay reflected. He’s probably right.

The Shift That Living Abroad Sparked in Him

One of the most unexpected takeaways from this conversation with Aikay was how living abroad reshaped his sense of empathy. It wasn’t that he never had it, but now he had seen things from a different perspective, and he explained. His experiences led him to rethink the entire framework of judgment we often use on others, especially when we say things like, “If I were you, I would have done this.”

According to Aikay, that’s a flawed way of thinking. He shared a personal theory — that if you were truly in someone else’s shoes, you would have their biology, experiences, height, complexion, trauma, joy, adrenaline levels, and even name, then you would do exactly what they did. This means you cannot actually be in someone’s shoes. It also means that the things that happen to us are not solely dependent on our choices; there are factors out of our control. He used to think he was invincible; if he was put in any situation, he would be able to overcome it by making the right choices. Now he understands that it’s not all about what we can do; sometimes in life, even when we don’t understand, life just happens.

He backed this up with a striking story. A friend once said he’d happily go to prison for 10 years in exchange for 10 billion Naira. Aikay used that as a launchpad to explain how, instead of complaining endlessly about Nigeria, someone could “disappear” for 10 years and build a medical career. In theory, it sounded airtight — study hard, get into a local medical school, grind for six years, ace your USMLE, move to the U.S., get matched into residency, and within ten years, you could be earning around $350,000 a year. It’s not 10 billion, but it’s still life-changing.

But then his friend reminded him that not everyone processes information the same way. Not everyone can “just pick up a book” and excel. Some people read for hours and still struggle to grasp the material. It was a wake-up call for Aikay. His mental model had been shaped by hard work as the ultimate virtue; he’d grown up seeing it from his dad constantly. But now, he realizes there are layers beneath the surface: psychological, psychiatric, and behavioral hurdles people face, often silently. We assume people are fine because they blend in, but that assumption can be dangerously superficial.

As he reflected on his return visits to Nigeria, it became clear: success often isn’t just about what you did or didn’t do. There’s a divine mystery in how paths unfold. Sometimes, we’re just beneficiaries of someone else’s labor, privilege, or timing. Acknowledging that doesn’t negate hard work; it just puts it in context.

Detours and Survival: How Aikay Ended Up in the Emergency Room

I remember Aikay being a pediatrician, so it was a surprise to learn that he now works in the emergency room. Does he like it there? No. Did he like pediatrics? No. Does he even like medicine? No. So, how did he end up in the emergency room? Here’s how it went.

As we’ve learned, medicine was something he fell into through a series of practical decisions. Aikay had to take several rounds of Nigeria’s postgraduate medical exams called the “primaries.” He first sat for the family medicine exam. After being rejected from all the limited programs available at the time, he tried community medicine, hoping it would be easier — it wasn’t. Still no success. Eventually, a job opened up in a pediatric hospital in Port Harcourt. People usually avoid pediatrics because it is considered a high-risk field. Aikay took it because he needed work. His boss there was kind, the kids were cute, and when asked if he’d consider pediatric residency, he said, “Eh, okay.”

He went on to pass his third set of primaries, this time in pediatrics, and was accepted into the first two interviews he attended. He chose one, started his residency, and that was it. Not because he dreamed of working with children, but because it was a means to an end.

But the grind in Nigeria soon became unsustainable. Resident doctors earned an average of ₦350,000 per month (approximately $230), which had to cover the cost of commuting to work, rent, car maintenance, and living expenses. It’s not a lot. He was being told to “get married,” to “move forward,” but how could he, when he was spending almost 20% of his income a month just on fuel? “I had to survive first before I start attaching titles,” he told me. The math wasn’t mathing.

That’s when Saudi Arabia came into the picture. A wave of Nigerian doctors was heading there, so Aikay followed. It was tough. He knew just enough Arabic to say “As-salamu alaykum,” and that was about it. Patients didn’t speak English. Initially, he wasn’t even seeing patients; instead, he rode in ambulances, helping transfer intubated patients from one hospital to another. Eventually, he picked up just enough medical Arabic to get by, but the cultural gap remained wide.

Still, Saudi surprised him. He expected a cold, rigid place, based on what he’d read online, but instead found some of the kindest people he’d ever met. That same shock came earlier in his life during the NYSC when he was posted to Ibadan. As an easterner, he was taught to be wary of Yoruba people. But what he found in Ibadan was a culture of humility, respect, and openness. To conclude his thoughts, he offers some unpopular advice. Many Nigerians don’t appreciate the NYSC and often don’t think it’s worth their time, but Aikay believes it’s very instrumental in experiencing different cultures firsthand, rather than through people’s word of mouth. “Go somewhere else; it might change your view of things,” he says nicely.

Accountability Isn’t Chauvinism — It’s Love

This part of the conversation is going to spark a mix of reactions. I teased my guest, Aikay, about the perception many have of him being chauvinistic. We’ve certainly sparred over this topic more than once, and I wasn’t going to let him off easy. But Aikay, as always, met the moment with a challenge: define chauvinism. What does it actually mean?

Pulling an Uno Reverse, I asked him what he thought people misunderstood about his stance on women, and his answer was clear: he believes in holding everyone accountable — equally. And for that, he claims, he’s often mislabeled. In fact, he went as far as saying he considers himself “one of the very few true feminists that exist in the world today,” by his definition of feminism, justice, fairness, equity, and accountability across the board.

To him, letting something slide just to avoid being called a chauvinist isn’t love — it’s negligence. He anchored his reasoning in scripture, referencing 1 Corinthians 13. Love, he said, is patient, kind, and does not rejoice in wrongdoing. So when he sees someone doing something he believes is wrong, like dressing inappropriately for a given occasion, he speaks up. Not because he wants to police people, but because, in his view, accountability is an expression of love.

One example he gave that made us both laugh (but also stirred the pot) was his “house help test” for defining indecent dressing. According to him, if a 22-year-old voluptuous house help wore something revealing in front of a woman’s husband, that woman would likely call it inappropriate. But when it’s that same woman dressing in a similar way, she justifies it as “my body, my choice.” Aikay’s point was that deep down, we often know what’s inappropriate; we just choose when and how to acknowledge it, depending on who’s involved.

Even with such strong views, I still feel safe around him. He’s someone I know would fight for my rights and protect me if it came down to it, despite our differences.

Ambition, Marriage, and Mutual Understanding

Now, the spark that made me bring Aikay on the podcast was a particular post I shared online that really triggered him. The post said, “There are many women who would love to sit at home and do nothing. Brothers, marry those women and leave ambitious women alone.” It went on to say that some women have a calling from God outside of marriage and that husbands who stifle their wives’ growth would answer to God for hindering His work.

Aikay boldly disagreed with this. Of course, on face value this seems very chauvinistic. But he went on to explain, and I started to understand. For him, the problem started right at the first slide. To him, it implied that women who stay at home lack ambition. He illustrated his point with a metaphor: “If you don’t like taking siestas at noon, don’t marry someone who takes siestas. Don’t call us who take siestas lazy.” His issue was the false equivalence. Staying at home doesn’t mean lacking drive. Homemaking, he argued, is an ambition for some women, and it’s unfair to frame them as less-than simply because their goals don’t align with mainstream career pursuits.

His second point was about the structure of marriage. Yes, marriage should bring out the best in both parties. But, he emphasized, it should function as a single, synchronized unit. If one person’s ambition — no matter how noble — starts to fracture that unity, then something’s gone wrong. Agree or not, Aikay brought clarity and conviction to a topic that’s often muddied by extremes.

Circling back to my original question, while I understood Aikay’s perception in a general sense, I had to offer a counterperspective, highlighting how tradition can sometimes become a trap.

For example, marrying a woman with vision and then trying to “clip her wings” in the name of structural submission. That this isn’t mutual decision-making, even referencing the Proverbs 31 woman from the Bible, who was both business-savvy and family-oriented. Ambition isn’t unbiblical; it’s misalignment and ego that cause disturbance. I believe the author of the post was likely speaking to men who marry ambitious women, knowing they’re “destined for greatness,” but then try to derail them due to their own discomfort in leadership.

Aikay initially had an issue with the word “ambition,” preferring “white-collar career path.” He emphasized that anyone can have ambition regardless of their career. Still, I argue that this post was targeted at a specific set of men — the ones who try to subdue their wives solely based on their egos.

Aikay’s perspective, however, is just as relevant. He argued that while men with those ego issues exist, there still has to be an understanding of not letting ambition ruin the family unit. During our conversation, he referenced a strategy that ChatGPT generated to destroy the world. One of the strategies it suggested was destroying the family unit. “I’ll weaken families. I’ll subtly erode the value of strong family units, stable relationships, and mentorship.” While ambition is something worth celebrating, he said, if something you’re doing is detrimental to the family unit, then it’s wrong.

We then shifted to the crucial aspect of pre-marital understanding. Aikay stressed that nobody becomes ambitious in marriage. An ambitious woman, he pointed out, was likely ambitious from her school days — a class prefect, a school prefect, active in university societies. This ambition is visible long before marriage. So, a man who marries her should have dated her long enough to know this about her.

After a long debate (and we spent a lot of time on this), we agreed it’s on a case-by-case basis. Sometimes it genuinely affects the family, but other times it stems from competition, an inferiority complex, ego, or even insecurities, like a husband being uncomfortable with his wife getting admiration at work. He proudly shared that he is a huge supporter and “cheerleader” for his wife, a medical doctor who was the best graduate student in her class. “Why?” He asks, “Because it is to the glory of the entire unit.”

In addition to this, sometimes new, unforeseen issues arise, like a child with special needs, then adjustments may be necessary. But springing up new “passions” that disrupt agreed-upon family plans is not ideal.

Ultimately, our conversation circled back to the importance of transparent communication and mutual understanding before and during marriage. It’s about agreeing on shared goals and supporting each other’s aspirations, without allowing ego or unforeseen expectations to derail what was once a clear path, while also making sure the family is growing together.

Let Your Body Grieve

Despite all the fun, we didn’t drift too much from this month’s theme: fathers. Aikay lost his dad recently and I was curious to know what he had learnt about grief since that time. “There is no formula,” Aikay said plainly. “Just grieve.” Whether it’s crying, isolating, or taking time to yourself, grief should be met with support, not shame. He made it clear that grieving looks different for everyone, and that difference should be honored. There’s no weakness in expressing it. “Men grieve too,” he added. “Men are more emotional than people would want to believe.”

He described how people cope in various ways: some become rebellious at work, some withdraw, and some cry constantly. Others swing to the other extreme — appearing overly cheerful, drinking, or distracting themselves in vague, unhealthy ways. His advice? Don’t repress it, but don’t turn to anything destructive either. “Just let it go. Pray about it, be open, and let your body handle it.”

Aikay gave an analogy that made perfect sense. He compared it to pregnancy — how each woman experiences it differently, with unique signs, timings, and rhythms. That’s how grief is. “However it is, your body… whatever it is at that point in time, you want to let it.” Discipline has its place when you’re training your body away from indulgence. But not during grief. “Grief is not one of the times you train your body. Grief is one of the times you let your body be.”

So if you want to cry, cry. If you want to sleep, sleep. If all your body knows to do is be still in sadness, allow it.

A Final Goodbye, Without Regret

Then came one of the most moving parts of our talk. I asked Aikay what he would say if he had one more conversation with his dad. Fortunately, his response was, “I said it to him. That’s why I was happy.”

Just weeks before his dad passed, they had a chance meeting in Lagos. Aikay had delayed his trip just to ensure they’d see each other. It turned out to be the last time. His father asked him to come over, prayed over him, and poured a whole bottle of anointing oil on him. “I didn’t know that was the last time we were going to see,” Aikay said.

Back in his hotel room, his dad began reflecting with a sense of unfinished business, regretful, wondering what he could have done better. But Aikay wouldn’t let him sit in that. He told him, “You are the best. Nobody has done it like you.” It was the most emotional moment they had ever shared. “You couldn’t have done it any better. You did a good job.”

He reminded his father of the fruit of his labor: three kids doing well — one in the U.S., two in the U.K. “There are so many parents that will look at our family structure and this is their dream,” he told him. “You have achieved things that most people wouldn’t achieve coming from where you came from.” His dad had raised righteous children, made massive sacrifices, lived a fulfilled life, and was respected and loved.

“If you die today, you died a great man,” Aikay told him. “You’ve done it all.”

He tried to get his dad to stop worrying about doing more. “No, relax,” he said. “This is the time we come and take care of you.” After they prayed, his father poured out the remaining oil. Aikay left with it still on him. They continued talking until his dad passed away not too long after. He was 76.

“Don’t Rush It”: Advice for Young Men Navigating Manhood

I couldn’t leave without getting some advice from Aikay for the younger generation. Especially men trying to be good sons, good fathers, or simply good humans. In response, he sings, “Father knows best.” And while we both acknowledged that not everyone has a present or loving father in their life, his point was clear: find someone who can pour wisdom into you. Find a voice of reason you can trust.

He didn’t shy away from acknowledging the mental strain many young people carry today. He’s seen 16-year-olds battling depression and feeling overwhelmed by life, weighed down by expectations and uncertainty. His advice was simple, yet so necessary in a world that often glamorizes fast living: “Don’t be in a rush.”

Aikay emphasized the importance of avoiding irreversible mistakes. He spoke candidly about how some people, including himself, didn’t always make the best choices. “We were just lucky,” he admitted. Things could have easily gone another way, not because of superior decision-making, but sometimes due to sheer grace.

So take your time. Let life unfold. And while you do, there are a few values Aikay believes every young man should prioritize: love for God, love for family, a genuine appreciation for education, respect for humanity, and love for yourself.

He was especially passionate about challenging the idea that “education is a scam.” It’s a narrative gaining traction, and one he finds deeply troubling. In its place, some are turning to shortcuts — fraud, OnlyFans, and other quick fixes that strip away dignity and depth. Education, he insists, is still foundational.

And finally, he circled back to the importance of self-love. If you truly love and respect yourself, you’ll respect others. That’s how you become a better man in this complicated, fast-moving world — not by racing ahead, but by staying grounded in the values that build character over time.

A Father’s Hope and the Power of Honest Conversations

As we wrapped up the episode, I asked Aikay a question I love to ask parents: If your children were to listen to this 20 years from now, what would you want them to hear about you? His answer was simple and heartfelt: “That I did good, and they were proud of me.” When I asked him to unpack what “good” meant, he said he hoped his kids would genuinely say, “We love you,” not just out of duty or habit, but because they meant it, and he could see it in their eyes. That alone, he said, would make him a happy man.

And then, in true podcast fashion, I slipped in one final question: What part of today’s conversation surprised you the most? He laughed and said it was the fact that we actually agreed on something. As someone who knows him well — and who knows how opinionated we both are — I had to agree, even though it took us 20 minutes. But it wasn’t about reaching consensus for its own sake. It was a moment of reflection for me, too. Having this conversation with someone who’s known me for 15 years gave me the chance to hear my own values out loud, to test whether they still held water. And to bring them back to Scripture — the objective standard that, for me as a Christian, ultimately matters most.

I also asked him what’s changed about me over the last 15 years, and his answer made me smile. He said not much had changed, this is exactly where he always knew I’d be. That I’d never settle for less than what I had envisioned. He admitted he was a bit surprised at how liberal I’d become, or at least how people-centered I am. And then he said something I’ll never forget — he made a cheeky comment about me being an African woman who speaks Korean and has a white child. It made us both laugh, but the admiration in his tone was clear: that’s who you are. Only you can make it seem so normal, and I admire that so much.”

He reminded me that conversations like these are rarely tidy — but they’re rich, they’re necessary, and they stretch us. And yes, friendship can survive differences, distances, and time.

So if you haven’t listened to the full episode yet, do yourself a favor — go listen. It’s a tribute to the dads we’ve had, the ones we’ve lost, and the fathers we hope to be. Whether you’re grieving, reflecting, or figuring it all out, this one’s for you.

🅻🅸🅽🅺🆂:

Download: https://mcdn.podbean.com/mf/web/kjfe9sfecpxiu332/AIKAY2025.mp3

Or on the website: www.mosibyl.com